Введение

Аутосомно-доминантная поликистозная болезнь почек (АДПБП) является наиболее распространенным наследственным заболеванием почек с частотой встречаемости от 1: 400 до 1:1000. На нее приходится 7–10% всех пациентов с терминальной хронической почечной недостаточностью (тХПН), что представляет собой серьезную социально-экономическую медицинскую проблему в мире [1, 2]. АДПБП – заболевание, обусловленное мутациями в генах PKD1, PKD2 или GANAB (PKD3). Мутации первых двух генов (PKD1 и PKD2) составляют 80–85 и 15–20% случаев соответственно [3, 4]. Заболевание характеризуется образованием и ростом кист в обеих почках, что приводит к снижению скорости клубочковой фильтрации (СКФ).

В конечном итоге большинство пациентов с АДПБП достигают терминальной стадии почечной недостаточности (тХПН). Однако возраст, в котором пациенты с АДПБП достигают тХПН, демонстрирует большую индивидуальную вариабельность даже между членами семьи, имеющими одну и ту же мутацию [5]. Прогнозирование скорости прогрессирования заболевания стало особенно важным в настоящее время с появлением толваптана, первого препарата, модифицирующего АДПБП [6, 7]. Для этого лечения следует выбирать пациентов с высокой вероятностью быстрого прогрессирования заболевания, поскольку для таких пациентов ожидается оптимальное соотношение пользы и риска [8, 9]. В настоящее время доступно несколько переменных для прогнозирования скорости прогрессирования АДПБП. СКФ является сильным предиктором, но менее чувствительна на ранних стадиях этого заболевания, когда СКФ может оставаться в пределах нормы за счет гиперфильтрации, а кисты продолжают формироваться [10]. Поэтому на ранних стадиях заболевания большое внимание уделяется общему объему почек как прогностическому показателю [10–12]. Считается, что на прогрессирование заболевания также влияет генотип АДПБП. Пациенты с мутацией PKD1 прогрессируют до тХПН быстрее, чем пациенты с мутацией PKD2 [13, 14]. Однако оценка генотипов на сегодняшний день дорогостоящая, а их связь со скоростью прогрессирования заболевания ограничена на уровне отдельных пациентов. Следовательно, перспективна разработка новых маркеров, которые сами по себе или в сочетании с обычными маркерами риска могут предсказывать скорость прогрессирования болезни.

Фиброз почек служит исходом различных хронических заболеваний почек и неадаптивного восстановления [15–18], характеризуется значительным накоплением и активацией интерстициальных миофибробластов, избыточным образованием и накоплением миофибробластами внеклеточного матрикса, который нарушает и заменяет функциональную паренхиму, приводя к органной недостаточности [19–21].

К компонентам экстрацеллюлярного матрикса (ЭЦМ) относятся коллагены, фибронектин, ламинин и другие протеогликаны. Их накопление в клубочках и тубулоинтерстиции происходит в результате дисбаланса между процессами синтеза и деградации/протеолиза. Ключевую роль в механизмах протеолиза играют матриксные металлопротеиназы (ММП). Протеолитическая активность ММП зависит от взаимодействия факторов, способствующих активации латентных про-ММП (плазмин, система урокиназа/рецептор урокиназы), и факторов, которые эти процессы ингибируют. Среди последних особое значение принадлежит тканевым ингибиторам ММП (ТИМП) и ингибитору активатора плазминогена I типа (ПАИ-I) [21, 22]. В физиологических условиях в почке функционирует сбалансированная система ММП/ТИМП, нарушение же баланса в системе ММП и их ингибиторов – один из механизмов развития ряда острых и хронических заболеваний почек [23, 24]. В последние годы активно изучается роль ММП и их ингибиторов в развитии и прогрессировании кистозных заболеваний почек. В эксперименте показано, что рост кист служит следствием увеличения синтеза компонентов экстрацеллюлярного матрикса при нарушении функционирования системы ММП/ТИМП [25].

В качестве предиктора прогрессирования АДПБП широко обсуждается общий объем почек [10, 26–28], увеличение которого, согласно литературным данным, более информативно, чем показатель СКФ [29–33]. При увеличении суммарного объема кист значительно возрастает степень тубулоинтерстициального повреждения и фиброза, а ММП и их ингибиторы играют ключевую роль в этих процессах.

В этом исследовании мы хотели показать ассоциации факторов протеилиза с характером течения АДПБП у детей с последующей возможностью и целесообразностью использования их в качестве факторов прогрессирования.

Цель исследования: определить уровень в сыворотке крови и экскрецию с мочой ММП-2, -3 и -9 и их ингибиторов ТИМП-1 и -2, ПАИ-I, установить связь их изменений с характером течения АДПБП, оценить значение нарушений в системе ММП/ТИМП в качестве дополнительного критерия прогрессирования АДПБП.

Материал и методы

В исследование были включены 36 детей с АДПБП (21 мальчик и 15 девочек), которые находились в отделении наследственных и приобретенных болезней почек им. проф. М.С. Игнатовой обособленного структурного подразделения «Научно-исследовательский клинический институт педиатрии им. акад. Ю.Е. Вельтищева» ФГБОУ ВО РНИМУ им. Н.И. Пирогова.

Медиана возраста пациентов на момент включения в исследование составила 13,0 (8,5–15,0) лет, медиана возраста девочек – 11,0 (8,0–14,0), медиана возраста мальчиков – 14,0 (9,0–16,0) лет, продолжительность катамнестического наблюдения (медиана длительности наблюдения – 4,0 (3,0–5,0) года.

Критерием включения в исследование стало наличие АДПБП у детей в возрасте от 1 года до 17 лет. Критерии исключения: солитарные кисты почек, аутосомно-рецессивная поликистозная болезнь почек, поликистоз почек в рамках наследственных синдромов (синдромы Шершевского–Тернера, Хиппеля–Линдау, Барде–Бидля, туберозный склероз).

АДПБП диагностирована у детей моложе 15 лет – наличие 1 или 2 кист в почках (одно- или двусторонних) по данным ультразвукового исследования (УЗИ) при наличии поликистоза почек у родственников первой линии родства [34, 35]; у подростков старше 15 лет – наличие более 3 одно- или двусторонних кист при наличии поликистоза почек у родственников первой линии родства [36]; мутация de novo предполагалась при наличии по данным УЗИ увеличения размеров почек и более 5 двусторонних кист в отсутствие отягощенного семейного анамнеза по АДПБП [37].

Функциональное состояние почек СКФ рассчитывалась по формуле G.J. Schwartz (Schwartz G.J. et al., 1987): СКФ (мл/мин/1,73 м²)=рост (см)/креатинин плазмы (мкмоль/л)×коэффициент, равный 48,6 у девочек и мальчиков младше 12 лет и 61,6 у мальчиков старше 12 лет.

В соответствии с классификацией хронической болезни почек (ХБП) Национального почечного фонда «Инициатива качества исходов болезней почек» (K/DOQI) [38] исходное состояние функции почек у всех детей с АДПБП соответствовало 1-й стадии ХБП, рСКФ 124,6 (107,7; 136,7) мл/мин/1,73 м2, рСКФ при катамнестическом обследовании – 117,1 (104,0; 128) мл/мин/1,73 м2. Ежегодные темпы снижения фильтрационной функции почек оценивались на основании рСКФ с учетом длительности катамнестического наблюдения и выражались в мл/мин/1,73 м2 в год: медиана -2,63 (-0,18; -5,13). Всем детям проводилось УЗИ почек с оценкой размеров, определением числа и размеров кист. При расчете объема почек по результатам ультразвуковой биометрии использовали формулу усеченного эллипса: объем почек (см3)=длина×ширина×толщина×0,53 [39]. У детей с АДПБП к определению вышеописанных показателей дополнительно, по визуальной оценке, сравнивали число кист в каждой почке, измеряли максимальные размеры кист, определяли суммарный объем почек с последующей коррекцией на стандартную поверхность тела и оценкой по центильным таблицам для исключения влияния возраста и роста. Скорректированный на поверхность тела объем почек облегчает правильную оценку объема почек ребенка независимо от возраста и выявляет патологическое отклонение от прежнего процентиля или z-значения, что важно при динамическом наблюдении и особенно ценно при наблюдении при АДПБП у детей [40].

АДПБП характеризуется прогрессирующим развитием и ростом многочисленных двусторонних кист почек, что приводит к различным нарушениям, наиболее важное из которых потеря функции почек. Повышение уровня креатинина не является чувствительным показателем прогрессирования заболевания, особенно у молодых пациентов. СКФ обычно остается в пределах нормы в течение нескольких десятилетий, несмотря на прогрессирующее увеличение почек. Компенсаторная гиперфильтрация в сохраненных нефронах изначально поддерживает содержание креатинина в сыворотке на уровне или около нормальных значений. Когда концентрация начинает заметно повышаться выше исходного уровня, более 50% функционирующей паренхимы разрушается. Oбщий объем почек достигает объема более 1 литра (нормальный размер менее 400 мл) до того, как произойдет потеря функции [41]. В настоящее время доступно несколько переменных для прогнозирования скорости прогрессирования болезни АДПБП. Индексированная по возрасту СКФ является сильным предиктором, но менее чувствительна на ранних стадиях этого заболевания, когда СКФ может оставаться в пределах нормы, а кисты постепенно формируются [42]. Поэтому на ранних стадиях заболевания большое внимание уделяется общему объему почек как прогностическому показателю [42, 43].

Для установления прогрессирующего течения АДПБП проанализирована скорость увеличения объема почек в динамике наблюдения. Всем детям, включенным в исследование, проводилось УЗИ почек при включении в исследование и при катамнестическом обследовании. Медиана долженствующего увеличения объема почек – 6,81 (5,83–9,0)% в год, у детей с АДПБП медиана увеличения объема почек составила 14,0 (9,9–22,8)%, медиана отклонения от долженствующего увеличения в год у детей с АДПБП – 114% (56,8–186,9). Прогрессирующим течением АДПБП считалось отклонение увеличения объема почек более 100% от долженствующего.

Для определения отклонения увеличения объема почек в год было оценено увеличение объема почек в год (% увеличения объема почек в год) и проведен сравнительный анализ с долженствующим увеличением объема почек у здоровых детей индивидуально в зависимости от возраста (согласно данным исследования, включившего более 3000 здоровых детей, в котором были получены референсные интервалы увеличения объема почек детей разного возраста) [44].

При включении в исследование медиана объема почек у всех детей, включенных в исследование, была статистически значимо больше, чем долженствующий объем, и составлял 226,7 (167,5–286,0) см3, тогда как долженствующий объем почек был равен 188,0 (130,4–215,0) см3, т.е. отклонение от долженствующей нормы составляло 27,7 (10,3–47,6)%. При катамнестическом обследовании общий объем почек у детей с АДПБП был равен 361,2 (255–469,8) см3, а долженствующий объем почек – 236,4 (208,4–262,7) см3, медиана отклонения от долженствующего объема почек составляла 52,5 (20,8–92,1) см3.

Пациенты были разделены на 2 группы в зависимости от характера течения АДПБП: 1-ю группу составили 26 (72,3%) детей с прогрессирующим течением; 2-ю – 10 (27,7%) детей с медленнопрогрессирующим течением.

В исследуемых группах с помощью иммуноферментного анализа проводилось определение уровня экскреции с мочой ММП-2, -3, -9-протеаз, расщепляющих основные компоненты ЭЦМ, а также ингибиторов ММП – ТИМП-1, Т-2 в моче, ПАИ-I в моче (первая порция утренней мочи в количестве 10 мл). Определение ММП-2, -3, -9, ТИМП-1, -2 в моче – с помощью набора реактивов ELISA/R&D Systems Quantikine, США; PAI-1 определяли с помощью иммуноферментного анализа реактивами фирмы «Technoclone» (Австрия). Исследования показателей в моче проводились с использованием метода твердофазного энзим-связанного иммуносорбентного анализа (Elisa-enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) на лабораторном счетчике Wallac 1420 Multilabel Counter (Victor 2) (Финляндия). Концентрацию медиатора в моче определяли по калибровочной кривой, которая строилась с использованием стандартных растворов с известной концентрацией, прилагаемых к набору реактивов. Для стандартизации уровня ММП и их ингибиторов в моче все показатели исследуемых детей пересчитывались на уровень креатинина в моче в мкмоль/л и выражались в мкмоль/мкмоль Сr.

Статистический анализ проводился с использованием программы IBM SPSS Statistics v.26 (разработчик – IBM Corporation) и GraphPad Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, США). Количественные показатели оценивались на предмет соответствия нормальному распределению, для этого использовался критерий Шапиро–Уилка, а также показатели асимметрии и эксцесса. При отличном от нормального распределения признаков оценивали медиану, разброс величин по отношению к медиане по показателю интерквартильного размаха (25–75 процентили). Номинальные данные описывались с указанием абсолютных значений и процентных долей.

При сравнении групп для независимых выборок по одному признаку использовался непараметрический критерий Манна–Уитни. Сравнение номинальных данных проводилось при помощи критерия Фишера. Различия считались достоверными при p<0,05.

Результаты

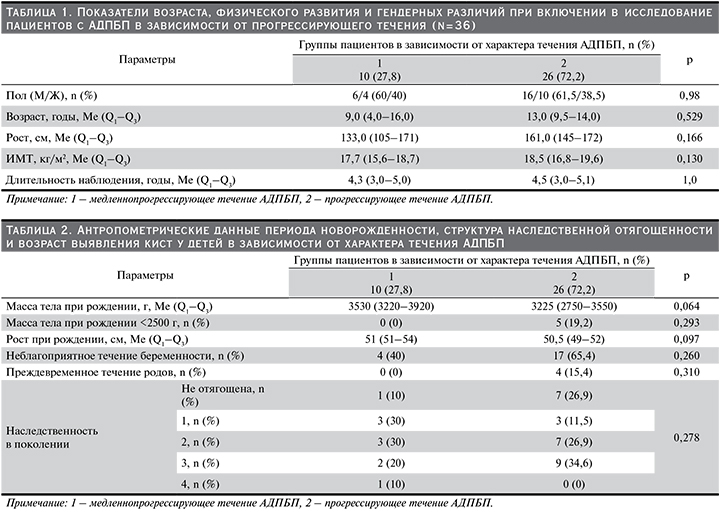

Дети с АДПБП в зависимости от характера течения были статистически сопоставимыми по полу, возрасту, росту, ИМТ, длительности наблюдения (р≥0,05) (табл. 1).

При проведении сравнительного анализа антропометрических данных периода новорожденности и структуры наследственной отягощенности в зависимости от характера течения АДПБП у детей статистически значимых различий не выявлено (р≥0,05), однако у детей с прогрессирующим течением заболевания отмечена более низкая масса тела по сравнению с детьми с медленнопрогрессирующим течением (р=0,06), также у 19,2% детей с прогрессирующим течением масса тела при рождении была менее 2500 г, тогда как при медленнопрогрессирующем течении этого не наблюдалось (табл. 2).

При проведении сравнительного анализа параметров фильтрационной функции почек у детей с АДПБП в зависимости от характера течения был установлен статистически значимо высокий уровень креатинина крови при катамнестическом исследовании:; 80 (68–94) и 61 (54–71) мкмоль/л (р=0,047), статистически значимо низкий уровень рСКФ при катамнестическом исследовании: 106 (103–120,5) и 124 (108–136,6) мл/мин/1,73 м² (р=0,041) и более быстрые темпы снижения рСКФ: -3,17 (-1,99–-6,96) и -0,57 (-0,2–1,80) мл/мин/1,73 м² (р=0,006) у детей с АДПБП с прогрессирующим течением заболевания, чем у детей с АДПБП с медленнопрогрессирующим.

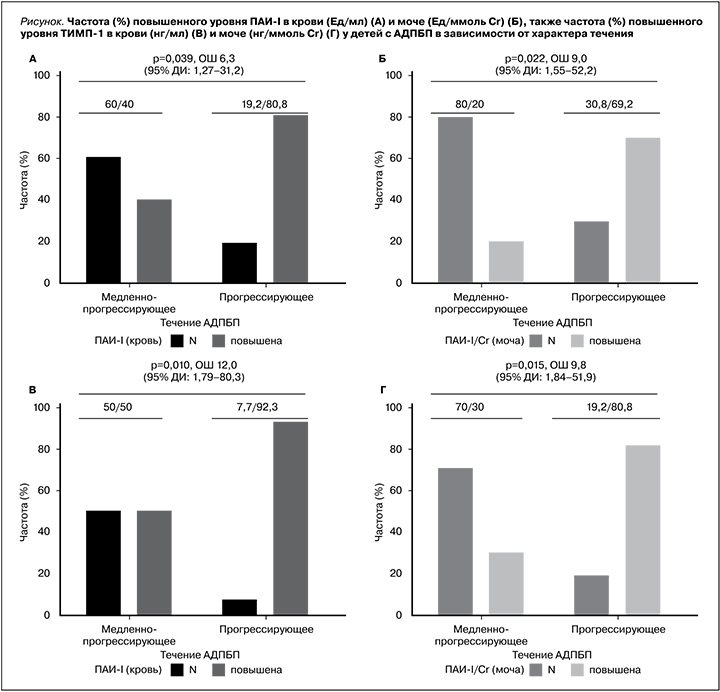

С целью установления связи факторов протеолиза в сыворотке крови и моче в зависимости от характера течения заболевания у детей с АДПБП проведен частотный анализ данных с помощью точного критерия Фишера. В результате анализа частоты изменений факторов протеолиза в крови и моче детей с АДПБП в зависимости от характера течения (медленнопрогрессирующее/прогрессирующее) получены следующие данные: у детей с прогрессирующим течением АДПБП частота повышения ТИМП-I в крови (р=0,010; V Крамера=0,479; отношение шансов – ОШ=12, 95% доверительный интервал [ДИ]: 1,79–80,3) и моче (р=0,015; V Крамера=0,482; ОШ=9,8, 95% ДИ: 1,84–51,9) статистически значимо было выше у детей с АДПБП с прогрессирующим течением заболевания. Также ПАИ-I в крови (р=0,039; V Крамера=0,396) и моче (р=0,022; V Крамера=0,444) статистически значимо было выше у детей с АДПБП с прогрессирующим течением заболевания. Шансы прогрессирующего течения увеличивались в 6,3 раза (95% ДИ: 1,27–31,2) в крови и в 9,0 раз (95% ДИ: 1,55–52,2) в моче по сравнению с медленнопрогрессирующим течением АДПБП (см. рисунок).

Обсуждение

Проблема ранней диагностики прогрессирования наследственных заболеваний почек у детей, таких как АДПБП, и выявление новых маркеров фиброза почек с целью предупреждения развития терминальной ХПН весьма актуально в современной нефрологии. Установление новых маркеров прогрессирования позволит дополнить имеющиеся факторы стратификации риска развития тХПН для своевременного начала терапии.

Прогрессирование заболевания достаточно сложно выявить на ранних стадиях АДПБП, прежде чем почечная функция будет значительно снижена, поскольку заболевание часто протекает бессимптомно, особенно у детей, также фильтрационная функция почек сохраняется длительное время за счет гиперфильтрации и не отражает морфологическую картину.

АДПБП – это прогрессирующее заболевание, в патогенезе которого наряду с увеличением объема кист важную роль играет тубулоинтерстициальное повреждение с увеличением эксрацеллюлярного матрикса и развитием тубулоинтерстициального фиброза [45], который рассматривается как патоморфологический субстрат почечной недостаточности [46, 47].

При увеличении суммарного объема кист значительно возрастает степень тубулоинтерстициального повреждения и фиброза, а ММП и их ингибиторы играют ключевую роль в этих процессах.

Прогрессирующий почечный фиброз служит результатом дисбаланса между образованием ЭЦМ и его деградацией. Выявление ранних биомаркеров фиброза почек имеет большое значение для пациентов с ХБП, поскольку раннее начало нефропротективной терапии может отсрочить развитие продвинутых стадий ХБП.

ММП представляют собой большое семейство цинксодержащих ферментов. В дополнение к основной роли в ремоделировании ЭЦМ они также расщепляют ряд поверхностных белков клеток и участвуют в многочисленных клеточных процессах [25, 47–49]. ММП могут быть вовлечены в инициацию и прогрессирование фиброза почек, в развитие ХБП [50–52].

По данным нашего исследования, в котором была проанализирована динамика изменения объема почек по данным УЗИ, скорректированного на поверхность тела, а также определены в сыворотке крови и моче факторы протеолиза, у 72,2% детей с АДПБП, включенных в исследование, было прогрессирующее течение заболевания. Проведенный анализ связи ММП и их ингибиторов в сыворотке крови и моче в зависимости от характера течения показал, что к факторам риска прогрессирования АДПБП у детей относятся повышение ТИМП-1 в крови (относительный риск [ОР]=7,14 [3,4–14,9]), чувствительность 88%, специфичность 65%, положительная прогностическая ценность 50%, отрицательная прогностическая ценность 93%) и в моче (ОP=3,64 [2,38–5,57], чувствительность 78%, специфичность 72%, положительная прогностическая ценность 70%, отрицательная прогностическая ценность 80%) и а также ПАИ-I в крови (ОР=3,1 [2,04–4,88], чувствительность 76%, специфичность 67%, положительная прогностическая ценность 60%, отрицательная прогностическая ценность 80%) и в моче (ОP=2,7 [1,94–3,65], чувствительность 72%, специфичность 78%, положительная прогностическая ценность 80%, отрицательная прогностическая ценность 69%). В литературе отсутствуют исследования связи факторов протеолиза у детей с АДПБП с тяжестью клинических проявлений, а также с течением заболевания. Однако доказано, что факторы протеолиза играют ключевую роль в расщеплении компонентов ЭЦМ, базальных мембран и цитоскелета клеток. Увеличение уровня тканевых ингибиторов ММП, сопровождающееся снижением уровня ММП, ассоциируется с усиленным накоплением фиброза в клубочках, особенно в интерстиции почки, что приводит к почечной недостаточности [24, 25]. Увеличение кист служит следствием увеличения синтеза компонентов ЭЦМ. Так, в исследованиях in vitro показано, что клетки почечных канальцев при АДПБП содержат большее количество компонентов ЭЦМ по сравнению со здоровой почкой [53], а в регуляции синтеза ЭЦМ, как показали экспериментальные работы, участвует система ММП/ТИМП. Установлено, что активное образование ТИМП и ПАИ-1, стимуляторами которого являются ангиотензин II и TGF-β1 (Transforming growth factor β1), приводит к снижению ферментативного расщепления компонентов ЭЦМ с последующим накоплением их в ткани почки, развитием тубулоинтерстициального и гломерулярного фиброзов [48, 49].

В ряде клинических и экспериментальных исследований продемонстрировано увеличение экспрессии ТИМП-1 и ПАИ-I в ткани почки по мере формирования тубулоинтерстициального фиброза и прогрессирования почечной недостаточности [54–56]. В литературе обсуждается вопрос, что ТИМП-1 связан с почечным фиброзом, является многофункциональным белком и избыточная эскпрессия ТИМП-1 может способствовать почечному интерстициальному фиброзу через воспалительные пути [57, 58]. Также в отечественной работе, исследовавшей роль факторов протеолиза в моче пациентов с разной активностью хронического гломерулонефрита, подтверждены провоспалительные эффекты ПАИ-I, реализуемые в интерстиции почек. Так, величина экскреции ПАИ-I с мочой прямо коррелировала с выраженностью клеточной воспалительной инфильтрации в интерстиции почек [46].

Заключение

Прогрессирование АДПБП в детском возрасте проявляется увеличением числа кист и размеров почек при сохранной фильтрационной функции почек длительное время за счет гиперфильтрации. Это исследование выявляет детей группы риска быстрого увеличения почек, т.е. прогрессирующего характера течения, которым в будущем могут быть полезны терапевтические вмешательства.

Полученные данные проведенного исследования свидетельствуют: ТИМП-1 и ПАИ-I могут рассматриваться в качестве факторов риска прогрессирования АДПБП у детей.